After heavy swells, if do it yourself enthusiasts in France enjoy finding driftwood on the beach, Lithuanians can easily find amber!

Amber is Lithuania’s gold. Baltic amber is a fossil resin, produced 40 million years ago by pine trees that were swallowed up by the Baltic Sea.

The gold of the Baltic coveted by the Egypt of the pharaohs…

The Silk Road is well known, but the Amber Road deserves to be better known. Amber was at the root of the first contacts between the peoples of the Baltic and the Mediterranean. Amber led the inhabitants of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, as well as the Arabs of the Near East, to organise the first trade routes to Northern Europe. In the French book Lituanie : Les feux de pierre, author Julien Oeuillet recalls that Baltic amber was even found on Tutankhamun’s mask!

…before inspiring the name of the greatest invention of the 19th century

The Lithuanian language associates amber with its protective properties. Amber is called gintaras (the verb ginti means to defend, to protect). The term gintaras refers to an amulet or good luck charm.

Romance languages as well as English associate amber with its potential uses. The term in these languages for amber was borrowed as early as the 14th century from the medieval Latin ambar, ambra, itself derived from the Arabic anbar, ‘ambergris’. Amber, of plant origin, was given this name by analogy with ambergris, of animal origin, which has similar physical characteristics and uses. Ambergris was imported into Europe in the Middle Ages for use as perfume and medicine.

When you touch it, amber captures body heat and releases it. In scientific jargon, amber is a combustible material and can cause electrification by friction (amber can generate static electricity when rubbed). According to a poetic Baltic legend, a piece of amber is a ray of sunlight that materialises when it comes into contact with water. Germanic languages associate amber with this notion of warmth and sunshine. The term Bernstein refers to amber’s ability to burn: it literally means ‘burning stone’ (from stein ‘stone’ and brennen ‘to burn’). And don’t the golden shades of amber remind you of fire?

The electrostatic properties of amber are recognised, so much so that the word electricity comes from the Greek elektron (ήλεκτρο) meaning amber!

…and making scientific discoveries possible even today

Imagine the scientific significance of this phenomenon: as it solidified, pine resin was able to trap intact, three-dimensional fragments of prehistoric living organisms! Animal and plant species: insects, spiders, fungi, lichens, bryophytes (a category of plants to which mosses belong), seed-bearing plants such as leaves, flowers, catkins and pollen, and so on.

The fossil floral archives in amber stand out for their rarity. Floral inclusions are generally no larger than 10 mm. One piece of amber, however, yielded a flower of exceptional size: 28 mm in diameter. The largest known fossil of a flower preserved in amber was found in the Baltic.

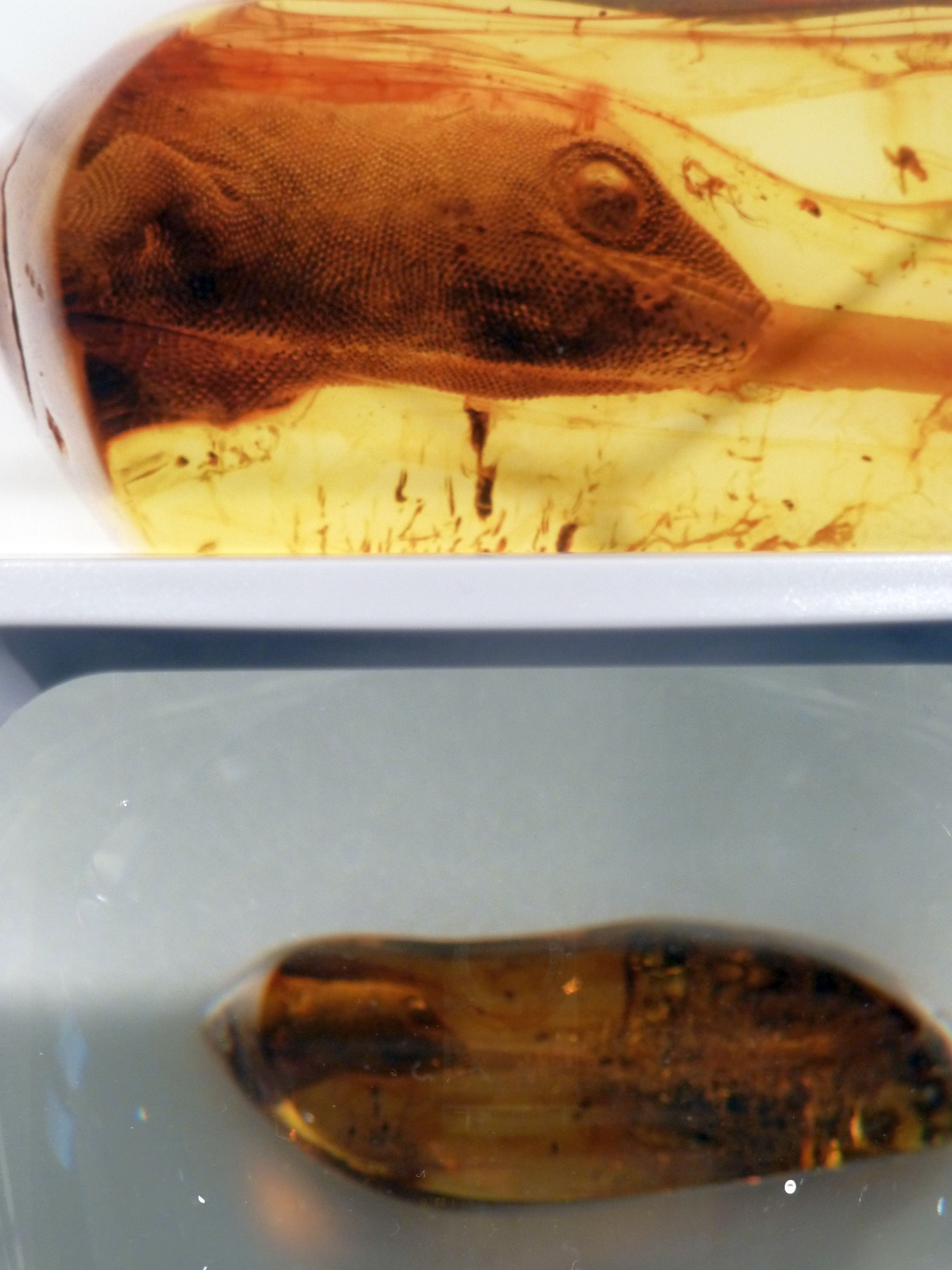

As for fossil arthropods, National Geographic estimates that Baltic amber has already yielded traces of more than 3,500 species (including more than 650 species of fossil spiders). What is even more amazing is that Baltic amber has masterfully preserved some prehistoric vertebrates, including the oldest known specimen of a variety of lizard: a gecko called Yantarogekko balticus, dated to around 54 million years ago! Its study led to the discovery that the gecko’s complex system for adhering its fingers to a wall is 20 to 30 million years older than scientists had thought.

A gecko called Yantarogekko balticus, dated to around 54 million years ago,

has reached us almost intact, thanks to a piece of Baltic amber.

Photo credit: Museumsfotograf

The world moves forward, and the Baltic Sea makes its contribution to this with fire in the belly!

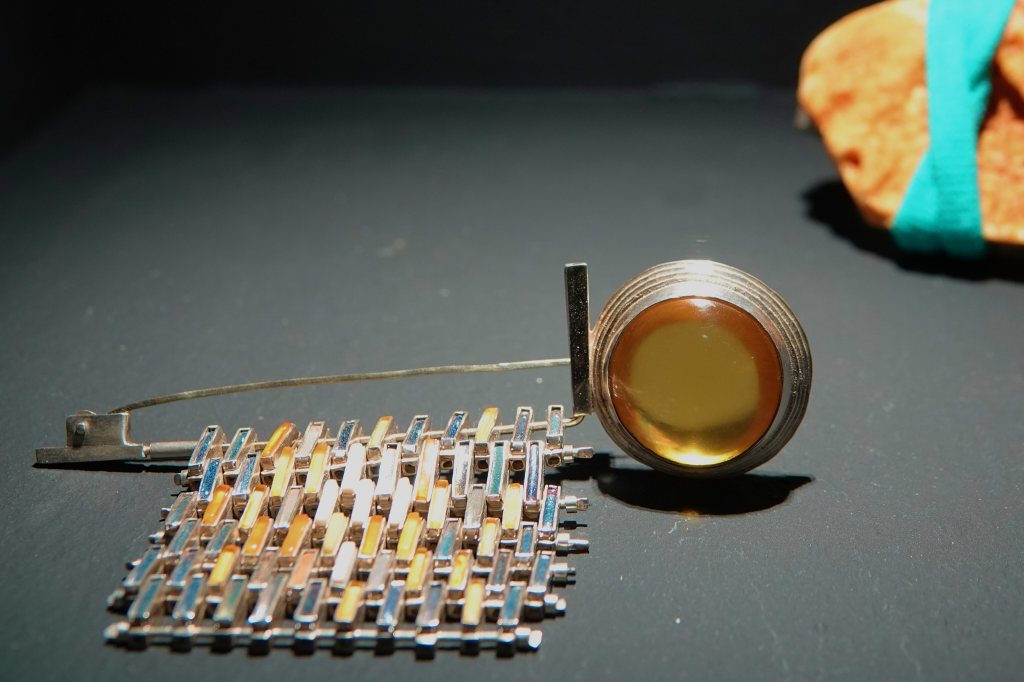

Headline photo of the article:

Vita Pukštaitė-Bružė

Brooch – ‘Reflection’, 2017

Amber, silver, gold, copper, enamel, mammoth bone

80 x 120 cm

Lithuanian Museum of Art

Photo credit: the author’s blog

Leave a comment